SHARP Grantee Spotlight

Can you give a brief history of your organization and your Humanities

Montana-supported project?

The Free Verse Project was formed in 2014 as a volunteer-only effort to bring weekly creative writing workshops to justice-involved youth incarcerated in Missoula County. In 2017, in collaboration with Young Poets, the Free Verse Project received three-year funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities for our project I Am Montana, which combines youth arts, writing, and humanities education with community outreach.

After receiving this funding, we were able to expand, holding arts-based workshops in five different youth facilities across Montana: the Missoula Juvenile Detention Center, the Billings Juvenile Detention Center, the Ted Lechner Youth Services Center in Billings, the Pine Hills Youth Correctional Facility, and the Billings Career Center.

Now in our seventh year, we have expanded further to include Cascade County’s Juvenile Detention Center and St. Patrick’s Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Unit, and our mission has solidified to encourage both incarcerated and non-incarcerated youth in these facilities to explore their identities as Montanans in creative ways and reflect on their understanding of the state and their experience within it.

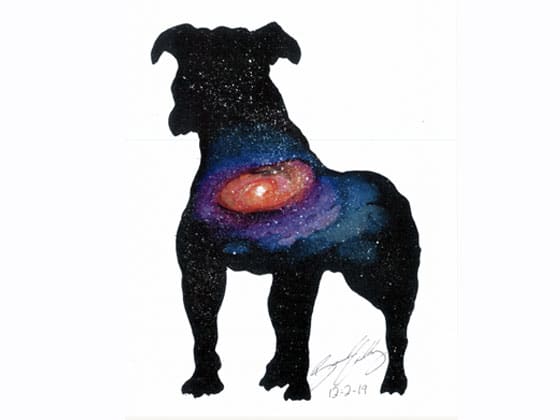

Each year, an anthology, titled I Am Montana, is published which features the creative works produced in these classes. We aim to amplify these lesser-heard and marginalized voices as they write a new narrative about what it means to be Montanan and contribute their unique voices to Montana’s artistic legacy.

In your opinion, what was the most notable accomplishment of your project?

We are very excited about the many new audiences connecting with the kids’ stories in the I Am Montana anthologies—among them college students studying at the Davidson Honors College at the University of Montana. Starting in 2020, the Davidson Honors College, acknowledging the unique types of knowledge and wisdom justice-involved youth in Montana have to share along with the literary merit of the writing, began teaching excerpts from I Am Montana alongside classic texts in a course called Ways of Knowing.

According to associate professor Lauren Collins, “For [college] students unfamiliar with the lived experiences of incarcerated youth not far from their own ages, these raw and intimate works communicated the agency and perspectives of the young authors, altering and deepening conversations we had in the classroom.” Professor Erin Saldin added that “[Our] students allowed themselves to be very vulnerable and to share their own experiences with the justice system, and we began a lengthy conversation about privilege and story that will continue until the end of the semester.”

In our mission to amplify justice-involved youth voices and widen the state dialogue to include the stories of incarcerated youth, having these anthologies and the kids’ creative works be incorporated into college curricula reflects the burgeoning community partnerships we’re excited about.

What lessons did you learn along the way?

One of the most important lessons we’ve learned over our seven years is how to evolve our workshop model to align with trauma-informed care best practices—especially the importance of building a rapport through consistency when working with the communities we serve, which have a significantly high number of trauma-impacted youth. Understanding that we have regular access to justice-involved youth, and the care necessitated, is something that we take very seriously; we require all staff members to undergo regular trauma-informed care training, and we intentionally craft our trauma-informed workshop plans to be as accessible and inclusive as possible. We’ve formatted our workshops to be consistent from session to session, so the kids we serve know exactly what to expect every time they come into a workshop with us.

We also learned the importance of being able to pivot our service provision when needed. In April 2020, all of the detention centers that hosted our workshops closed their doors to in-person visitors due to the pandemic—understandably, considering the ongoing spread of COVID-19 and its disproportionate impact on people who are incarcerated. And ironically, it was those facilities’ closures that offered us an opportunity to increase the frequency of our workshops. In response, we shifted fairly quickly to a virtual model, which enabled us to continue offering our programming on a regular, consistent basis, much more consistent than previously, due to the long distances of most of the facilities to our staff based out of Missoula. For example, while in the past we were only able to travel out to Miles City to work with the youth in Pine Hills Youth Correctional Facility once or twice a year, our virtual workshops allowed us to Zoom into their classroom on a weekly basis, which allows us to do more in-depth, consistent work.

What’s your definition of the humanities?

The humanities respond to, capture, and engage with the voices and stories of communities and then share those voices and stories through art, literature, history, and languages. They’re a vehicle to communicate—across time and cultures—those fundamental aspects of our natures. That’s why it’s so important that, with the support of sponsors like Humanities Montana, we’re able to bring these creative workshops to this particular community. Many of these kids, who are disproportionately of color and from lower-income homes, have seen their stories left out of our wider state narrative. As kids who are incarcerated, their voices often go unheard, their faces literally hidden behind walls, erasing them from their communities, their families.

What’s more, incarcerated youth are often dismissed out of hand as delinquents or dangerous, without being invited to tell their own stories. By giving often-marginalized Montana youth the chance to collaborate in order to understand, interpret, and speak to their own experiences, we hope to bring these vital voices into our state’s conversations. Through public exhibits, lectures, and dialogues, we hope to create communities that understand and acknowledge the diverse experiences of their neighbors, their youth, and all Montanans. I Am Montana aims to provide a platform for these young voices to be heard, shared, and honored.

What advice can you offer to future Humanities Montana grantees?

Humanities Montana has been hugely encouraging of our project over the years and always eager to communicate with us, answer questions, and support us as we’ve grown and expanded our scope. It’s been exciting to share the results of our programming, including through photos, excerpts of stories, and student responses. My best advice to future grantees is to carefully record project progress as you go, throughout the grant timeline—create a folder and drop photos, snippets of conversation, press, any feedback received along the way from the individuals or communities you’re working with—so that when the project is completed, you have a healthy and complete archive you’ve compiled throughout the year to share with Humanities Montana.